|

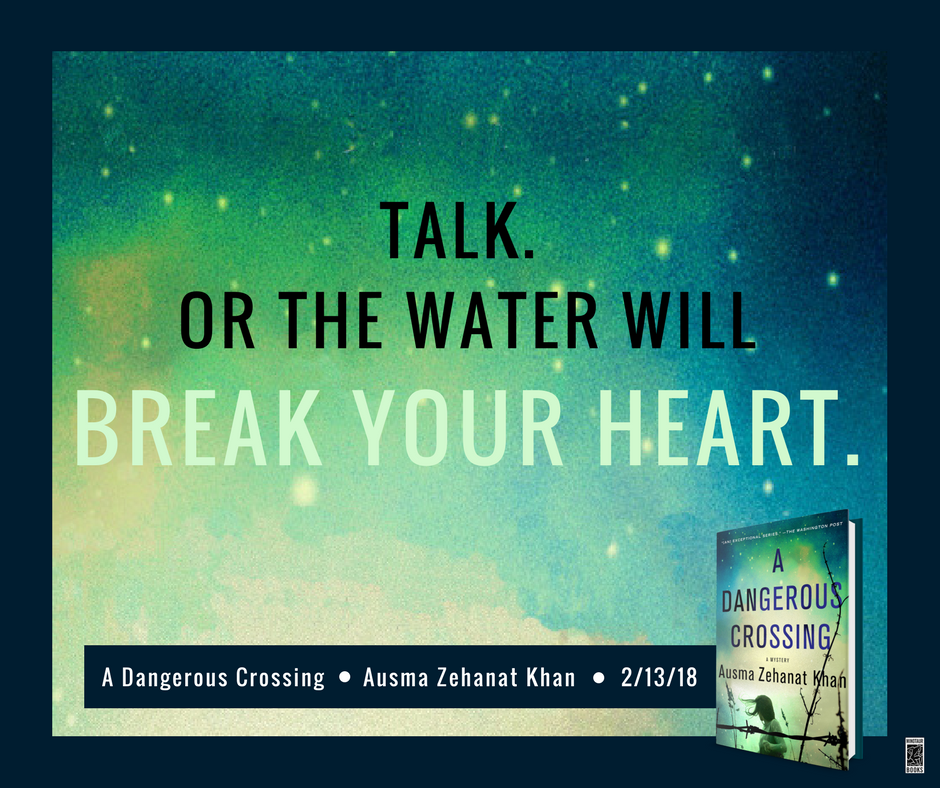

It's publication day for A DANGEROUS CROSSING. The book is like a ship setting sail into the world, and I ran a contest using several of the most significant lines in the book. This one reflects the book distilled to its essence. And now as A Dangerous Crossing sets sail, I hope it will relieve the weight on my heart--the ever-present weight that was the reason I wrote it. I hope that the people who were courageous enough to speak to me about their experiences on all sides of the crisis will feel that the book treats their stories with clarity and respect. I hope that the book will make a difference to people's perceptions of the refugee crisis and the dire need of refugees around the world--particularly in Syria. I hope for a free Syria one day, with peace and dignity and freedom. I hope for an accounting at the Hague.

|